Astonished that the Department for Health feels it can make long-term policy, planning and commissioning decisions without having in-depth knowledge of the scope and depth of the issue.

In 2016, the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child recommended the UK and its devolved administrations must:

“Rigorously invest in child and adolescent mental health services and develop strategies at the national and devolved levels, with clear time frames, targets, measureable indicators, effective monitoring mechanisms and sufficient human, technical and financial resources. Such strategy should include measures to ensure availability, accessibility, acceptability, quality and stability of such services, with particular attention to children at greater risk, including children living in poverty, children in care and children in contact with the criminal justice system;”

Unfortunately, we are a long way from this vision of a robust and effective mental health system for our children and young people.

Anyone who knows about my time as Commissioner will be aware that mental health has been one of my main priorities since the day I took up post in March 2015.

My office has explored the area of child and adolescent mental health through talking with children and young people, their parents and carers and professionals, as well as examining the available evidence and data relevant to this issue.

As our work progressed, it became even more apparent to us that this is a significant issue for the children and young people. You can read our scoping paper which sets out the human rights basis for mental health, and the data and evidence concerning children and young people’s emotional well-being and mental health.

Through doing this we have gained some clarity on where we should focus our work in order to fill gaps and complement and inform the work of others. Our approach is threefold:

Firstly, whilst we know that young people are concerned about their mental health I have come to appreciate how difficult it often is for them to get the right support when they need it. Alongside this we have been hearing from community based counselling and support organisations, who are expected to do a lot more with a lot less. Thresholds for access to formal CAMHS (Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services) are getting higher (that is children have to become increasingly unwell before they can access these services), leaving community based organisations to support many more vulnerable children than they have previously.

It is has become clear that we do not know enough about what actually happens to children and young people when they seek help or support across the system. This includes within the community (from voluntary and community based organisations), through schools, GPs, the formal child and adolescent mental health service, the criminal justice system or in other ways. We have insufficient detailed information about a child’s journey and experience of going through these processes; what worked well or not so well? was the process of seeking help straightforward or were there barriers?, was support offered in a timely way or did young people have to wait? If young people are not accepted by services, why is this? and what other form of support is being offered? The questions go on. It is troubling that we have insufficient detail on, or any way of understanding, the actual experiences of our young people.

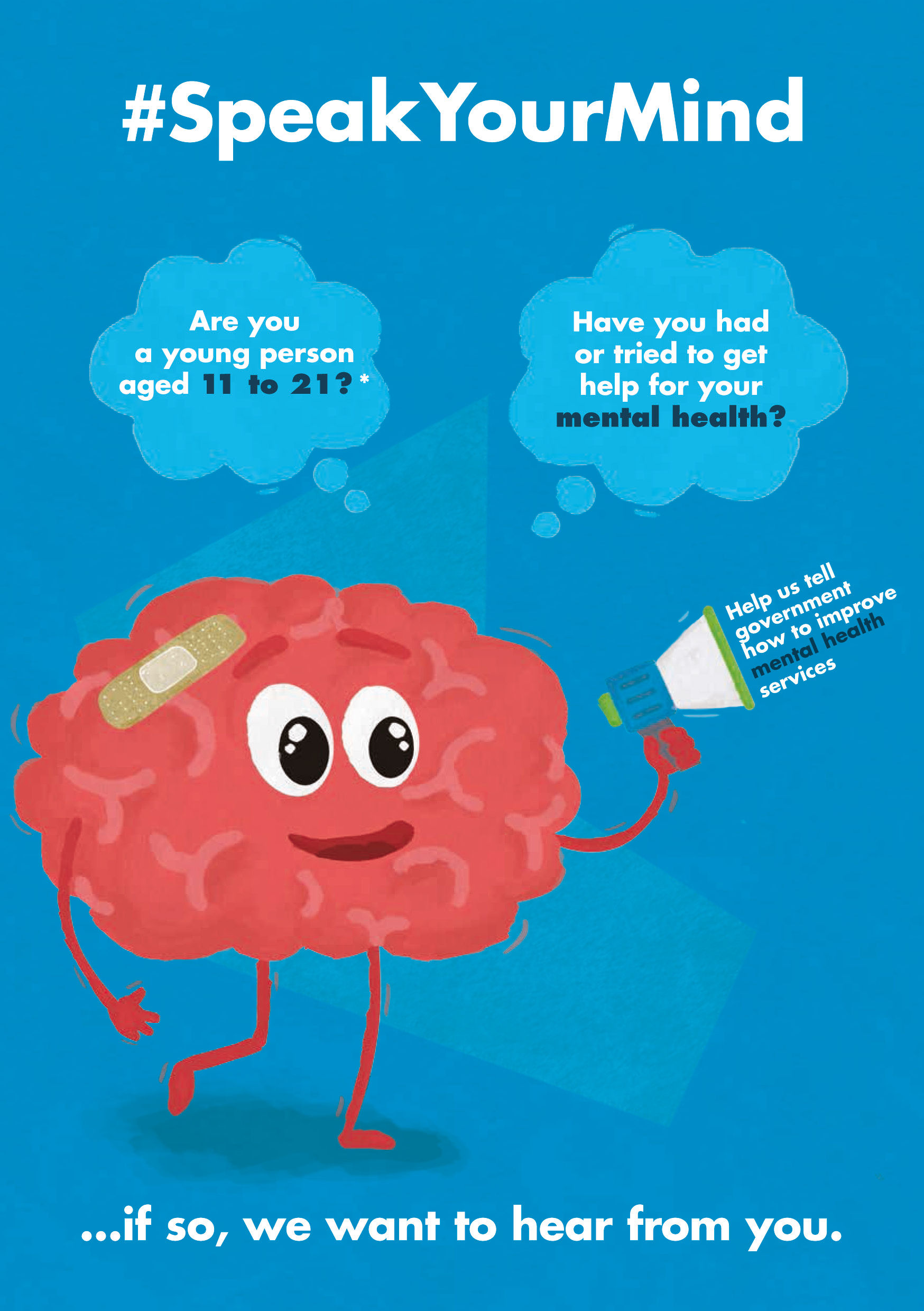

NICCY, advised by our advisory board of academics and researchers and members of our Youth Panel, has designed and now launched a survey for young people (aged 11-21) which will enable them to share their experiences with us.

In view of the detail that the survey asks for, we are very conscious that young people may need some support and would ask those adults who know them well, to do so when they feel it might be necessary.

We are also keen to hear the views and experiences of parents and carers and would encourage them to complete the parent and carer survey.

Secondly, In the coming months we will be meeting with specific groups of young people who have particularly complex needs, have higher rates of poor mental health but face the most significant challenges in accessing mental health services and having an appropriate response to their needs.

Finally, in Northern Ireland we fall short of having sufficiently robust information on our children and young people’s mental health and the services that support them. It is deeply disturbing that NI recently opted out of participating in the UK prevalence survey of children’s mental health, citing finances as the main reason. This type of survey is used to gather information about the prevalence of mental disorders in order to inform policy decisions about child and adolescent mental health services. I am astonished at the notion that the Department for Health feels that it can make long-term policy, planning and commissioning decisions without having an in-depth knowledge of the scope and depth of the issue.

It is also very concerning that there is limited robust and disaggregated regional data on key operational aspects of the CAMHS system, including a lack of a standardised monitoring framework across Health and Social Care Trusts.

For this review we will be collating the data that is available, to better understand the availability, accessibility and quality of services, this includes a more detailed understanding of the allocation of funding of mental health services for children and young people.

There needs to be much greater clarity and understanding of children’s and young people’s mental health needs, and on the evidence base being used by Government to shape policy and practice, identify unmet need and direct resource. It is impossible to know if the needs of children and young people are being met or whether better outcomes are being achieved, if neither are being effectively recorded or measured.

Once this work is completed in 2018, we will make the findings publicly available. We will use the findings to provide detailed and thorough advice to government on the best way to improve the mental health and emotional wellbeing of our children and young people, by being much clearer about how we should respond to it.